/********

Dies ist ein temporär stabiler Explainer über den Subjektentwurfs des Dividuums. Ich editiere hier immer mal wieder rum, nicht wundern.

********/

Das Dividuum ist ein Subjektentwurf, der sich als semantische Pfadalternative zum Individuum positioniert. Genauso wie das Individuum ist das Dividuum einzigartig, aber anders als das Individuum ist das Dividuum kein abgeschlossenes Ganzes, dass der Welt gegenüber steht, sondern ein Verkehrsknotenpunkt für Milliarden Netzwerke.

Genaugenommen ist das Dividuum dadurch sogar viel einzigartiger als das Individuum, denn während alle Individuen aus denselben Zutaten bestehen, also „Geist/Intelligenz“ und „Körper“, kann man ähnliches nicht für Dividuen sagen. Jedes Dividuum ist ein wilder, einzigartiger Mix aus allerlei Welt, die in es hineinragt.

Deswegen lässt sich auch nur wenig Allgemeines über das Dividuum sagen, außer, dass es immer an einem ganz konkreten Ort in der Welt ist und zu einer konkreten Zeit und wenn man die Zeit laufen lässt, wird das Dividuum zum Pfad. Der Pfad hat ein Anfang und ein Ende und um diesem Pfad entsteht und verändert sich Infrastruktur, die wiederum die Welt der anderen Dividuen beeinflusst.

Das Dividuum ist eigentlich erst ein nützliches Modell, wenn man es in eine Welt setzt, also seine Dimensionen betrachtet. Im Gegensatz zum Individuum lebt es nicht in seinen Infrastrukturen, sondern ist seine Infrastrukturen und das stimmt auf dreifache Weise:

- Materiell: Die ganze Agency des Dividuums realisiert sich über seine ihm zur Verfügung stehenden Infrastrukturen, also Pfadgelegenheiten.

- Psychologisch: Das Dividuum subjektiviert sich entlang und über die Verfügbarkeit seiner Infrastrukturen (siehe unten).

- Sozial: Das Dividuum ist immer wieder selbst in vielen Belangen Pfadgelegenheit für andere, also eine Infrastruktur für dieses und jenes.

Die materielle Geschichte des Dividuums

Das Dividuum entstand aus Notwehr. Mein Argwohn gegen das Individuum trug ich schon länger mit mir rum und natürlich kannte ich bereits viel der philosophischen Kritik am Individuum, aber mit Kritik ist es ja nicht getan. Wenn man so tief in den Eingeweiden der westlichen Perspektive herumdoktort, hat man ein Problem: Alle möglichen Erzählungen, Konzepte, Begriffe und nicht zuletzt all unsere Selbsterzählungen, unsere Subjektivierungen sind Pfadabhängig vom Subjektentwurf des Individuums. Und ich will mich ja auch morgen noch, naja, subjektivieren. Deswegen war mir klar: ich brauche eine plausible Pfadalternative, die die pfadabängigen semantischen Verbindungen des Individuums übernimmt. Einen Bypass.

Ich hatte ein paar grobe Ideen eines vernetzten Subjektentwurfs und hatte zu diesem Zweck im Newsletters schon einiges an semantischer Infrastruktur zusammengesammelt und als ich die Pfadgelegenheit sah, verkündete ich in Krasse Links 27 meinen offiziellen Austritt aus der Kirche des Individualismus.

Ich hatte mir das lange überlegt, aber ausschlaggebend war letztendlich dieser Ted Talk von Deb Chachra über Rolle von Infrastrukturen in unserem Leben.

Ich kommentierte den Talk so:

Infrastrukturen sind das, was Deine „Agency“ überhaupt ermöglicht und damit auch Deine Fähigkeit, Dich als Individuum zu erleben.

Und als ich dann noch mit Ishay Landa im selben Newsletter verstand, wie der Transmissionsriemen zwischen Individualismus und Faschismus funktioniert, war für mich das Maß voll.

Okay, hier ist mein Deal: Ich habe aufgehört, ans Individuum zu glauben. Ja, es gibt Akteure, die Dinge anstoßen, aber wir alle navigieren nur innerhalb vordefinierter Strukturen. Wir können nur navigieren, weil uns zu jedem Zeitpunkt immer nur so und so viele Optionen zur Verfügung stehen, unsere Geschichte weiterzuerzählen. Wir sind also Opportunisten und alles was wir tun, ist mit den uns zur Verfügung stehenden semantischen Schablonen nach Pfadgelegenheiten Ausschau zu halten, um auf ihnen durchs Leben reiten.

Diese Gelegenheiten werden wiederum von Infrastrukturen bereitgestellt, materielle wie semantische und weil wir uns nun mal im Kapitalismus bewegen, ist eine besonders netzwerkzentrale Infrastruktur das Geld. Zugang zu dieser Ressource ermöglicht Zugang zu vielen anderen Ressourcen und damit Pfadgelegenheiten. Aber Eigentum/Geld/Preise sind nur ein Abstraktionslayer, den wir als Zugangsregime über einen Großteil unserer Infrastrukturen gelegt haben. Im Alltag erleben wir Normalos Geld deswegen als den entscheidenden Flaschenhals, der unsere individuelle Navigationsfähigkeit ermöglicht und begrenzt und damit das absteckt, was Lea Ypi neulich „horizontale Freiheit“ nannte.

Was Landa hier beschreibt, stelle ich mir konkret so vor: Leute, die vergleichsweise viele Pfadgelegenheiten vor sich zu haben gewohnt sind, also wir Mittelstandskids aus dem Westen, haben uns eingeredet, bzw, einreden lassen, dass wir Individuen sind. Das Framework des „Individuums“ erlaubt es uns auszublenden, dass sich unsere Freiheit aus den vielfältigen materiellen und semantischen Infrastrukturen speist, die unsere Vorfahren und andere Menschen um uns herum gebaut haben, bzw. bauen und maintainen. Statt also unsere Eingebundenheit in diese Strukturen anzuerkennen, reden wir uns seitdem ein, wir hätten unseren „Wohlstand“ „erarbeitet“ und wenn wir es materiell zu etwas gebracht haben, schließen wir daraus, dass wir besonders „intelligent“ sein müssen und damit auch individueller als andere Menschen.

Und dann schauen wir auf andere Menschen, deren Infrastrukturen ihnen deutlich weniger Pfadgelegenheiten bieten und unser Individualismus-Framing deutet diese mangelnde Agency dann als verminderte, oder gar abwesende Individualität, also ein Mangel an Intelligenz und/oder Zugehörigkeit zu einer „rückständigen Kultur“. Das ist der materielle Kern dessen, was Judith Buttler mit „Abjectification“ meint und es ist die Rutschbahn vom Liberalismus zum Faschismus, auf der gerade der gesamte Westen gleitet. Huiiii!

Den ersten Schritt, den man tun muss, um das Dividuum zu denken, ist vom Glauben abzufallen. Denn wir alle sind Gläubige in der Kirche des Individuums und man wird das mistige Ding nicht los, wenn man sich dessen nicht bewusst wird und aktiv Widerstand leistet.

Der zweite Schritt ist, die Pfadalternativen zu entwerfen. Im selben Newsletter sah ich den Fluchttunnel noch in Haraways „Cyborg“ und das ist immer noch metaphorisch richtig, aber aus formalen Gründen bin ich dann doch beim „Dividuum“ gelandet. Dennoch gilt, was ich hier über Cyborgs schreibe, auch für das Dividuum.

Cyborgs sind defizitäre, bedürftige Wesen, die auf ihre Infrastrukturen angewiesen sind, um und zu überleben. Und nur weil die Cyborg kein Individuum ist, heißt das nicht, dass sie ohne Agency wäre. Die Agency des Cyborgs speist sich nicht aus ihrer „Vernunft“ oder wie es heute heißt, „Intelligenz“, sondern aus den materiellen und semantischen Infrastrukturen, die ihr zur Verfügung stehen.

Die Cyborg lebt in den Infrastrukturen und ist die Infrastruktur. Sie arbeitet an den Infrastrukturen, baut sie, betreibt sie, hält sie in Stand. Als höfliche Pfadopportunistin navigiert sie die Schmerzarchitektur zwischen Arbeit und Konsum und versucht mittels der ihr zugänglichen Infrastrukturen ihre Geschichte weiterzuerzählen. Diese Geschichte ist ein Pfad im Netzwerk, der von der Vergangenheit bis ins Jetzt und durch Pläne, Ziele und Projekte bis in die Zukunft weitererzählt wird.

Die Cyborg ist Dividualistin. Sie beobachtet nicht die Welt, sondern beobachtet wie andere die Welt beobachten. Sie surft auf diesen Beobachtungen, Worten, Bildern, Gesten und Geschichten und sortiert sich in ihnen ein. Gleichzeitig sendet jede ihrer Bezugnahmen einen Impuls durchs semantische Netzwerk, weil sie ja ihrerseits beim Schreiben, Sprechen, Denken beobachtet wird.

Es kann sich nur noch um Minuten handeln, bis die Cyborg begreift, dass sie die Infrastruktur ist und den Laden übernimmt.

Die dividuelle Subjekterfahrung habe ich in Krasse Links 26 so skizziert:

Und jetzt kann man, wenn man will, die Intention wieder reinlassen, aber nicht mehr als eine aus sich selbst heraus sprechende Stimme, die sagt „ich will“, sondern als Navigator, Surfer, oder Trommler.

Navigator, weil wir zu jedem Zeitpunkt immer an einem konkreten semantischen Ort im Raum stehen, wann immer wir handeln. Das heißt, wenn wir irgendwo hinwollen (etwas sagen oder denken), müssen wir Schritt für Schritt von dort nach da hin-navigieren und unsere Fähigkeit zu Sprechdenken besteht, wie bei der LLM, vor allem aus allerlei gemerkten Weganweisungen.

Man kann das auch Surfen, wenn man etwas firmer mit einer bestimmten Semantik ist. Dann verknüpft man die vorbeifliegenden Sinn-Ereignisse wie Wellen, auf denen man reitet. (yeah!)

Und zuletzt drücken wir auf „Play“ und nehmen die Zeit mit dazu und dann beginnt sich dieses Netzwerk langsam aber stetig auf uns zuzubewegen. Semantiken verschieben sich, verwandeln sich, werden größer oder kleiner, zentraler, peripherer, mutieren, streuen, sterben, etc. Und wir sehen immer neue Ereignisse eintreffen, die immer neue Narrative aufs Gleis setzen. Die Narrative wiederholen sich, referenzieren sich, zitieren sich und in stetiger Wiederholung und Bekräftigung werden sie erwartbar und strukturieren wie ein Beat unsere Zeit und geben uns Orientierung nach vorn.

So richtig eingeführt habe ich das Dividuum in Krasse Links No 28, in dem ich anlässlich meines Textes über KI und Semantik Derrida mit Haraway und Deleuze verbinde.

Wie schon Derrida sagte: Wir sprechen nicht, wir werden gesprochen. Das bedeutet nicht, dass man nicht auch neue Pfade finden kann, aber eben immer nur an den Rändern des bereits Gedachten und Gesagten. So wie die Nordpolexpiditionen erst machbar wurden, als die Infrastrukturen es erlaubten, so sind auch neue Gedankengänge nur als Verlängerung oder Abzweigung bereits existierender Routen denkbar. Es gibt kein Punkt außerhalb des Netzwerks.

Der Text selbst ist ein gutes Beispiel: Er basiert offensichtlich auf einer poststrukturalistischen Infrastruktur, aber wäre auch ohne Donna Haraway nicht denkbar. Mit ihrem „situierten Wissen“ stellte sie den Poststrukturalismus vom Kopf auf die Füße und ermöglicht, die richtige Perspektive aufs Netzwerk zu finden. Wenn Bedeutung stetiger Aufschub, aber dabei stets situiert ist, dann passiert Schreiben, Sprechen, Denken immer an einem ganz bestimmten Punkt eines ganz spezifischen Kontextes. An diesem je spezifischen „Hier und Jetzt“ gibt es immer nur eine überschaubare Zahl an plausiblen Pfadgelegenheiten, von denen man sich von einer zur nächsten stürzt. Wenn man dann die Zeit anstellt, bewegt sich der Punkt durchs Netzwerk und wird zur Linie, bzw. ein Pfad oder eine Route. Fertig ist die LLM, bzw. Sprechen und Denken.

„Die Individuen sind ›dividuell‹ geworden, und die Massen Stichproben, Daten, Märkte oder ›Banken‹.“ Schreibt Gilles Deleuze im „Postskriptum zu den Kontrollgesellschaften“ bereits Anfang der 1990er und verabschiedet damit Foucaults „Disziplinargesellschaft„, die sich noch auf die Zurichtung des Individuums und der Organisation von Masse konzentrierte. Aus dem Unteilbaren (lat. individuus) wird etwas per se Teilbares (lat. dividuus).

Das Navigieren in der Semantik – Schreiben, Sprechen, Denken – ist ein dividueller Akt. Man beobachtet nicht die Welt, sondern man beobachtet einander, wie man die Welt beobachtet. „Dividuell“ bedeutet also, sich selbst als Teil des Netzwerkes zu imaginieren, das Sprache, Denken und Öffentlichkeit und Infrastrukturen hervorbringt.

Es ist den Zitaten anzumerken und relevant zu verstehen, dass sich der Subjektentwurf des Dividuums parallel und in ständiger Korrespondenz mit der Enststehung der Semantiktheorie entwickelt hat. Das Dividuum ist ohne „semantische Pfadgelegenheiten“ nicht denkbar, bzw. es ist andersrum: Man kann das Individuum nur dann denken, wenn man Semantik nicht denkt und dann die Stimme in eigenen Kopf für ein unverbundenes „Res Cogitans“ hält, das als Agent einen Körper durch die Welt steuert, mit dem man sich dann fälschlicher Weise identifiziert. Und genau da ging und geht ja der ganze Schlamassel mit der Infrastrukturvergessenheit seit Descartes schon los, der uns gerade im Gesicht explodiert.

Klar, im Vergleich zum Individuum kann das Dividuum erstmal nicht viel. Das Dividuum hat keine Eigenschaften und „tut“ auch nichts, es ist halt ein Netzwerkknoten, der vollständig durch seine Verbindungen definiert ist. Und ausgerechnet durch Verbindungen, die nicht wirklich dem Dividuum gehören, sondern teil von Netzwerken sind, in deren Interaktion das Dividuum eingebunden ist und danach strebt sich darin temporär zu stabilisieren. Zu diesen Netzwerken gehören biologische Netzwerke, genetische Netzwerke, Bakterielle Netzwerke, Blutkreisläufte, Nährstoffkreisläufe, Klimakreisläufe, städtische Infrastrukturen, Gesetzesframeworks, Produktionskreisläufe, Lieferketten, die Sprachen, die ich spreche, Diskurse an denen ich teilnehme, die Geschichten die ich mir und anderen erzähle, mein Emailprovider, die Straßenbahn und die regelmäßigen Bedürfnisse meines Hundes.

Im Gegensatz zum Individuum, das in sich selbst ruht, hat das Dividuum einen ständigen Hang zur Instabilität. Das Dividuum ist immer im Flux, weil sich all die Verbindungen, aus denen es besteht, ständig verändern. Einerseits wechseln Dividuen ständig ihren Ort in der Welt, d.h. verlieren ständig Verbindungen und gewinnen neue. Andererseits verändern sich die Verbindungen selbst, weil sich die Welt verändert. Deswegen ist das Dividuum den Gezeiten und Turbulenzen seiner Netzwerke ausgeliefert und wird wie eine Boje im Wasser von den Wellenbewegungen im Netzwerk hin und hergeschüttelt. Das Resultat ist ein ständig instabiler Dividuums-Knoten, der die ganze Zeit damit beschäftigt ist, die veränderte Beziehung in einem Netzwerk, durch Veränderung von Beziehungen im anderen Netzwerk auszutarieren (dafür braucht es allerdings Pfadgelegenheiten).

Ohne seine Pfadgelegenheiten ist das Einzige, was das Dividuum „kann“, also „beeindruckt sein“ von der Welt. Aber genau in dieser strukturellen Berührbarkeit steckt der epistemische Wert des Dividuums: Im Sich-Verhalten des Divduums zur Welt verbrigt sich ein struktureller Spiegel der Gesellschaft. Man muss nur den Beat hinter dem Tanzmove erkennen.

Das Dividuum in der Philosophie

Ich selbst habe das Konzept des Dividuums wie gesagt von Deleuze, aber so unbekannt der Begriff wirkt, hat er doch eine überraschend lange Theorietradition. Schon Nietzsche weißt auf die gespalten- und uneinheitliche Motivationsstruktur des Indviduums hin und spricht vom „Selbst“ als ein Divduum. Auch in der Anthropologie wurde der Begriff immer mal wieder gebaucht, etwa von Marilyn Strathern.

Der französische Phliosph Gilbert Simondon sprach zwar selbst nicht vom Individuum, aber seine Individuation-Theorie sollte einflussreich für die Dividualist*innen werden, insbesondere für Deleuze und Anderea Ott. Aufbauend auf Simondons Prozess-Ontologie der Individuation – in der jedes Individuum nur eine vorläufige Stabilisierung in einem überschüssigen, prä-individuellen Feld ist – beschreiben neuere Theorien das Dividuum als Knoten in dynamischen Relationen, als nicht-abgeschlossene Einheit.

Michaela Ott entwickelt daraus den Begriff der „Dividuation“ als heuristisches Werkzeug einer Philosophie der wechselseitigen Abhängigkeiten, Teilhabe, während Gerald Raunig das Dividuum zum Leitmotiv einer Analyse des maschinischen Kapitalismus macht: Die gleiche Teilbarkeit des Subjekts, die Plattformen und Finanzmärkte zur Extraktion nutzen, eröffnet zugleich molekulare, „kon-dividuelle“ Formen der Gegenmacht.

Ich habe überall nur reingelesen bisher, aber gut zu merken, dass ich mit meinem Dividuum als Teil eines eingespielten Rhythmus trommle.

Wie funktioniert dividuelle Subjektivierung?

Die traditionellen Subjektivierungs-Theorien sind natürlich individualistisch und damit unbrauchbar. Foucault und Buttler haben die individualistische Subjektivierung aufgebrochen, aber für unser Dividuum schlage ich einen einen Entwurf vor, der sich eher an Emanuall Levinas und Donna Haraway orientiert und den ich die Dividuelle Subjektivierung nenne.

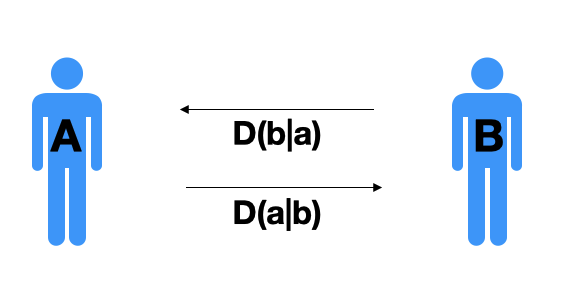

Dividuelle Subjektivierung ist die Art und Weise, wie wir uns selbst in dem Anderen und den Anderen in uns sehen, bzw. differenzieren.

Diese „Art und Weise“ ist wiederum ganz grob das Set an pfadabhängigen Unterscheidungen, die ich zum Erkennen der Differenzen in der Wiederholungen des Anderen in mir verwende.

Beispiel: Wenn ich mich als „Individuum“ entwerfe, entwerfe ich alle anderen um mich herum auch als Individuum, aber eben als andere Individuen, jedes ein „unteilbares“ „Bewusstsein“ in einem Körper in der Welt. Außer die ohne Agency – das sind im besten Fall „tragische Fälle“, aber oft auch „Versager“ oder bei manchen Menschen sogar „Abschaum“, also grob das was Judith Buttler „Abjection“ nennt.

Aber auch abseits des Individuums verstehen wir Subjektivierung als die tägliche Praxis des mich im Anderen erkennen und differenzieren, nach einem bestimmten Schema von Unterscheidungen.

Aber das Schema von Unterscheidungen ist natürlich sozial konstruiert. Klar, durch Infrastrukturen der Disziplinierung, durch Diskurshoheiten, Gesetze, Normen, Rollen und ihre sozialen Hierarchien und Ausgrenzungen. Aber auch durch teils über tausende Generationen geerbt und verinnerlichte und nie hinterfragte Unterscheidungen. Aber unsere Unterscheidungen kommen auch aus Gesprächen auf der Arbeit oder beim Sport, Büchern oder Newslettern, die wir gelesen haben, News die wir mitbekommen haben oder über das neuste Tiktok-Meme. Oder wir sammeln unsere Unterscheidungen aus den Geschichten aus dem Kino, das aber auch nur dieselben Narrative immer wieder anders erzählt, von denen die meisten aus der Antike stammen. Da gibt es ehrlich gesagt auch gar nicht so viel Spielraum, denn um zu funktionieren, müssen Narrative anschlussfähig an bereits erwartete Narrative sein, so wie ein Satz anschlussfähig an den vorherigen Satz sein muss und ein Wort an das vorherige Wort.

Diese soziale Co-Produktion von Wirklichkeit und Subjekt kann man auch mit Federico Campagna als Worlding bezeichnen. Aus Krasse Links No 20

Im Zentrum seiner Theorie, oder wie er sagt: „Metaphysik“, steht das „Worlding“: Welt, aber als Verb. Worlding ist etwas, was wir konstant tun: wir bauen und aktualisieren unser Weltmodell. Aber dieses Weltmodell ist natürlich kein individuelles, sondern eine geteilte Semantik, ein Vibe, ein „Rhythmus“, wie er es auch nennt. Es gibt also Weisen des Worldings und sie bilden die unbewussten und unhinterfragten Axiome unseres Weltverständnisses oder wie ich immer sage: die Art, wie wir auf die Welt blicken.

Wordling ist semantisch, d.h. wir haben uns unser Worlding in den seltensten Fällen ausgesucht, sondern haben es zum Großteil geerbt und auch ansonsten kreieren wir es zusammen: wir „worlden“ gemeinsam, miteinander, aber immer wieder auch gegeneinander, wobei man sich das „Worlden“ wie einen Beat vorstellen kann, den alle um einen herum tanzen, ein Vibe in dem man fühlt, und machmal auch der Beat, den „die anderen nicht haben“.

Ein Resultat dieses gemeinsamen und wechselseitigen konkurrierenden Worldings nennen wir auch „Wirklichkeit“ und ich muss in diesen Zeiten nicht extra darauf hinweisen, wie schief das gehen kann.

Das andere Resultat des Wordings ist eine bestimmte „Perspektive“, bzw. die semantische Seite unserer Perspektive. Perspektive ist ja zunächst einmal der materielle Ort in der Welt, von dem ich sehe und spreche und ist somit vor allem geprägt, durch die mir zur Verfügung stehenden Infrastrukturen und den Abhängigkeiten, die sich daraus ergeben.

Doch die semantische Seite der Perspektive funktioniert über das „Worlding im Anderen“ – als Navigation der eigenen Erwartungen an mich selbst im Raum der Erwartungserwartungen der anderen.

Die semantische Perspektive ist von der materiellen Perspektive nicht unabhängig. Je nach den Infrastrukturen, die ich gewohnt bin, zur Verfügung zu haben, kann ich mir andere Subjektentwürfe plausibel machen oder auch nicht.

Beispiel: In Krasse Links No 31 hatte ich einmal die materielle Geschichte des Subjektentwurfs des Individuums umrissen:

Das Individuum erblickte das Licht der Welt in den europäischen Salons der besseren Gesellschaft des späten 18. Jahrhunderts, als die Oberschicht wechselseitig an sich feststellte, wie schwerelos das Leben ist, wenn man Hausangestellte hat. Genau genommen haben sie den letzten Teil ausgeblendet, genau so wie die Tatsache, dass sich die Agency ihres Hauspersonals auf Arbeiten oder Hungern beschränkte und ihnen also das Individuum gar nicht plausibel war.

Das Virus sprang schnell über zu den Sklavenhaltern in den USA und perkulierte entlang der sprießenden Infrastrukturen der Industriellen Revolution immer weiter in die Gesellschaft hinein (überall wo Lebensstandards einen bestimmten Schwellenwert an Pfadgelegenheiten erreichten), bis das Individuum so ab 1900 zum Mainstream wurde. Mit Strom, fließend Wasser, Telefon und Auto wurde das Individuum zum Lebensgefühl des 20. Jahrhunderts und zum Grundbaustein der Metaphysik des Westens.

Der Subjektentwurf des „Individuums“ kann überhaupt erst plausibel werden, wenn einen die Welt mit einen bestimmten Threshold an Pfadgelegenheiten ausstattet.

Das heißt, man muss sich bestimmte Subjektentwürfe leisten können und viele Subjektivierungs-Pfade stehen aus bestimmten Perspektiven überhaupt nicht zur Verfügung oder sind nicht plausibel. Der Subjektentwurf des „Superindivuums“ zum Beispiel wird erst ab Milliardär plausibel, aber auch die ganzen anderen materiellen Statusgames dazwischen könnt ich mir eh nicht leisten (außer son bisschen Applehardware, ok).

(Werbehinweis: Einer der Vorteile des Dividuums ist, dass es sehr „affordable“ ist. Sogar die Amöbe könnte sich das Dividuum leisten, würde sie subjektivieren.)

Ja, man kann aus Subjektentwürfen ausopten, und das ist, was wir hier machen, aber auf einer tieferen Ebene, was das Projekt früher oder später extrem schwierig machen dürfte.

Denn Subjektentwürfe sind auch Macht. Simone de Bauvoire machte darauf aufmerksam, dass die Subjektentwürfe „Frau“ und „Mann“ soziale Konstruktionen sind, die die gesellschaftliche Funktion haben, das Patriarchat am Ruder zu halten. Auch Foucault kannte die Macht der Subjektentwürfe aus schmerzhafter Erfahrung und schrieb sein Werk nicht zufällig zu einer Zeit, als sich neue Subjektivierung-Pfade Bahn brachen und die hegemoniale Weisen des Worldings und der Subjektivierung aus dem Takt brachten. Buttler und die Intersektionalist*innen haben die Subjektivierung weiter ausdifferenziert, indem sie sie aus den „Kategorien“ befreit haben und sie stattdessen als vieldimensionale Erfahrungslandschaft dachten. Das Dividuum baut auf dieser Tradition auf.

(Werbehinweis: Das Dividuum ist beliebig erweiter-/ausdifferenzierbar und macht alle Dimensionen des Lebens darstellbar..)

Subjektivierung ist nicht nur narrative Selbst-, sondern immer auch Welt-Reproduktion. Das Dividuums-Subjekt ist weder Ursprung noch Endpunkt von irgendwas, sondern nur die sich ständig aktualisierende Form einer Dividuum-Welt-Relation, die sich im gemeinsamen und wechselseitigen Worlding stabilisiert.

Dividuelle Subjektvierung ist das stetige Anwenden und gleichzeitige Einüben der eigenen Perspektive an und anhand des Anderen.

Deswegen reicht es auch nicht das Dividuum zu „verstehen“ oder zu „denken“. Zumindest, wenn man, wie ich, aus der Individuums-Perspektive kommt, muss man das Dividuum als alternativen Subjektivierungspfad erst mühsam einüben und ich bin da auch erst am Anfang, tbh. Aber diese andere Perspektive ist real und die ganzen Beobachtungen, die ich hier teile, wurden erst durch diese Perspektive möglich.

Das Dividuum ist also das Projekt eines anderen Pfads der Subjektivierung, das andere Formen des Worldings erlaubt. Es ist eine Häresie, basically. Oder wie ich es in Krasse Links öfter nenne: eine semantische Sezession.

Die Perspektive des Dividuums

Hinweis: dieser Abschnitt ist noch sehr unfertig, braucht noch wesentlich mehr Tiefe. Diese Beschreibung der dividuellen Perspektive ist also kein fertiges und vollständiges Modell, sondern eine spekulative Sammlung von Mindestanforderungen an ein dividuelles Perspektivmodell an dem ich immer mal wieder weiter rumpuzzel.

Perspektive ist die Art, wie wir auf die Welt schauen.

Im Gegensatz zur Perspektive des Individuums, das vor sich Objekte und andere Individuen zu sehen glaubt, ist die Perspektive des Dividuums vielgeteilt: Sie ist die Summe unserer Eindrücke und die Summe unserer plausiblen Pfadgelegenheiten an einem Ort, sowie die Summe der erinnerten Pfadabhängigkeiten hinter uns, die implizite Zeugenschaft der Anderen und die Geschichte, die das alles zusammenhält.

- Ort: Jedes Dividuum ist an einem Ort. Der Ort grounded die Perspektive.

- Eindrücke: Alles, was sich in das Individuum eindrückt. Semantiken helfen dabei, die Eindrücke zu unterscheiden.

- Materielle Pfadgelegenheiten: Alle Unterscheidungen, die das Dividuum nutzt, um sich in die Zukunft zu projizieren. Pfadgelegenheiten bilden die Agency des Dividuums. Plausible Pfadgelegenheiten bilden den Raum, in dem wir planen und entscheiden.

- Semantische Pfadgelegenheiten: Pfade in den erwarteten Unterscheidungen der anderen, aber auch der eigenen.

- Plan. Imaginierter Pfad im Netzwerk der Pfadgelegenheiten zu einem Ziel.

- Pfadabhängigkeiten: Der Pfad von dem man herkommt, die Erinnerung.

- Die Erwartungen der anderen/Erlaubnisstrukturen. Der durch die Subjektivierung verinnerlichte Blick des Anderen. Auch bekannt als „Gewissen“ oder „Überich“.

- Emotion/Empathie. Emotion und Empathie sind dasselbe, denn jede Emotion ist bereits semantisch.

- Aufmerksamkeit. Der Fokus des Dividuums auf die aktuellen Unterscheidungen.

- Motivation. Das Orientierungsschema der Pfadselektion.

- Geschichte: Jedes Dividuum verbucht Eindrücke, Pfadabhängigkeiten und Pfadgelegenheiten in eine Erzählung über sich selbst. Diese Geschichte ist der schwammig erinnerte und nur stellenweise dokumentierte Pfad durch das Leben des Dividuums entlang eingeübter Narrationsstrukturen bis zum Jetzt.

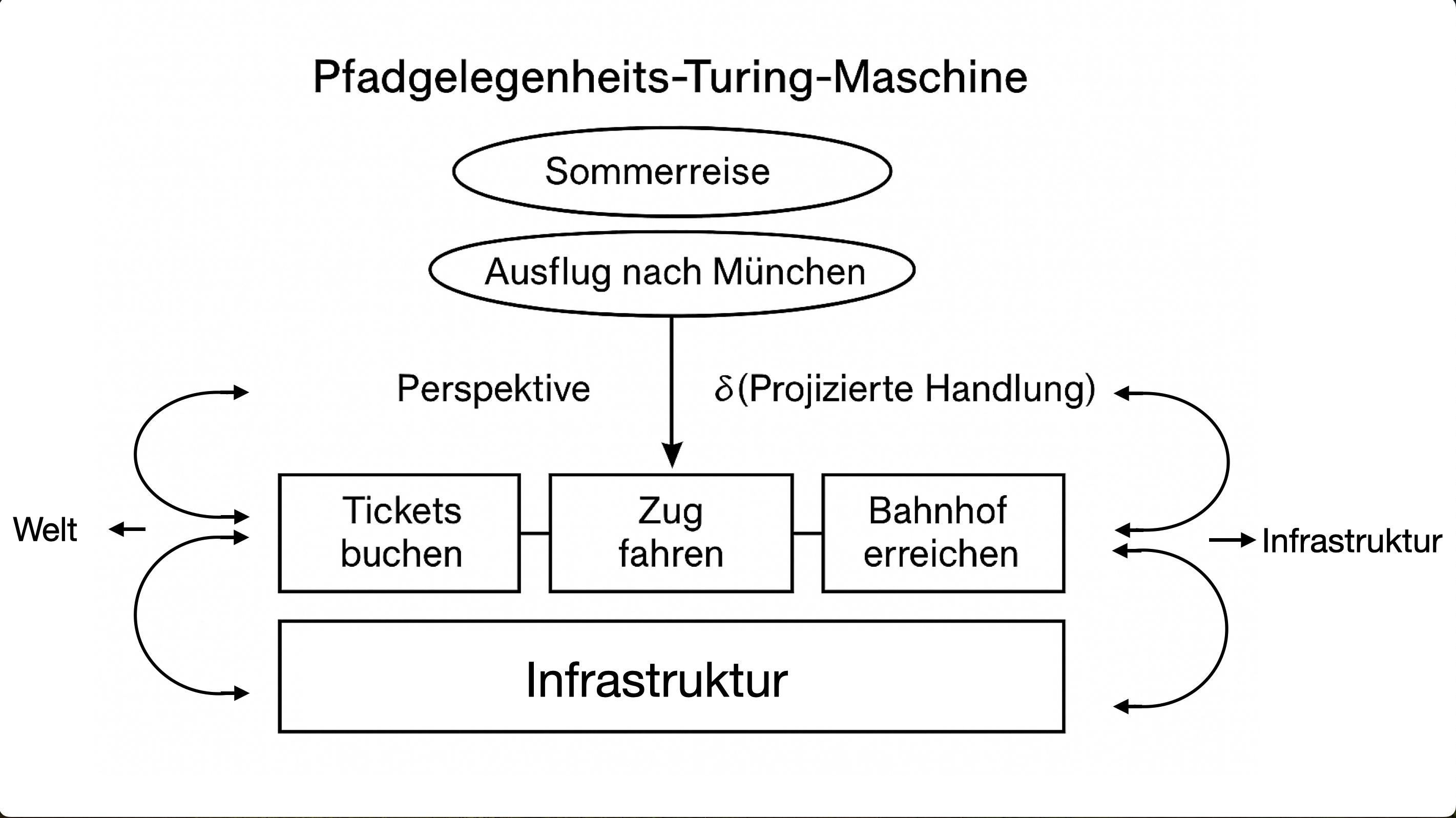

- Pfadgelegenheits-Turing-Maschine. Der Prozess der Umwandlung von Pfadgelegenheiten in Pfadabhängigkeiten und Geschichte.

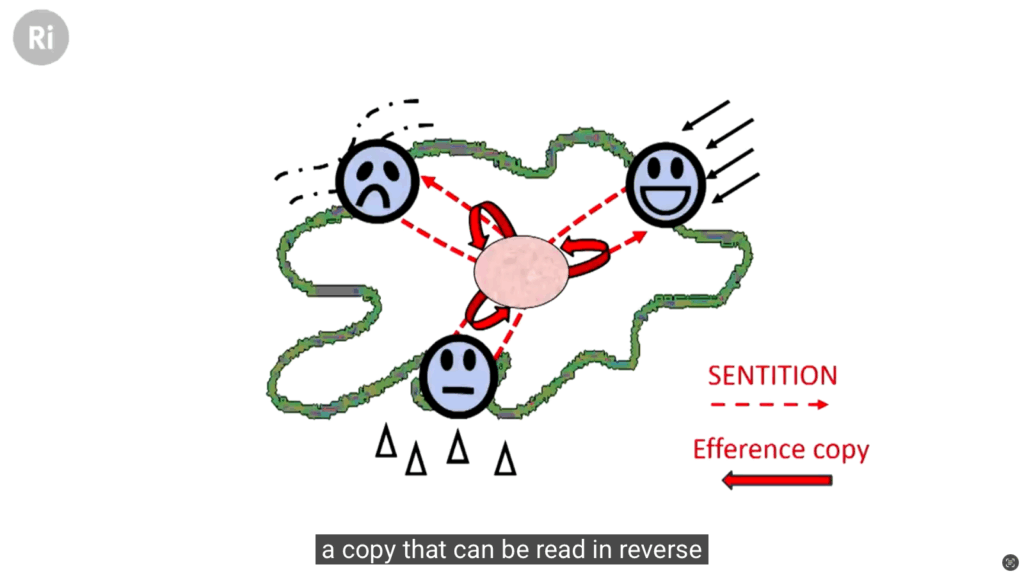

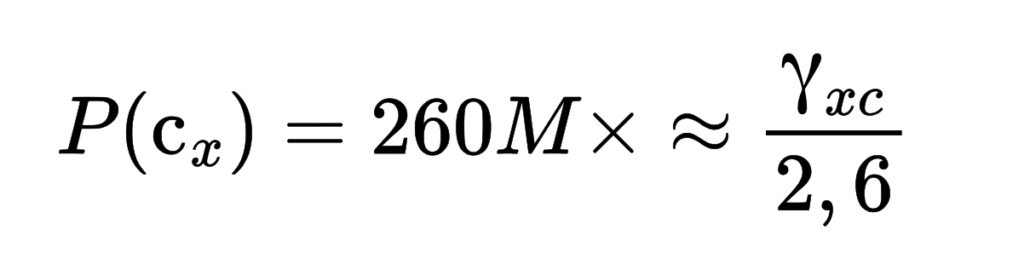

Bild: Dividuelle Perspektive.

V.o.n.u.: Pfadgelegenheiten (semantisch und materiell) streben zur „Geschichte“, aber müssen dafür den „Blick des Anderen“ (links oben) passieren, um zur „Pfadentscheidung“, also und pfadabhängiger teil der „Geschichte“ zu werden. Das „Q“ an den Pfeilen der Pfadgelegenheiten steht für „Q-Function“ (siehe Pfadgelegenheits-Explainer), also der Evaluation des Pfadgelegenheits-„Werts“ durch das Dividuum, bevor es die Pfadgelegenheit nimmt. Erst durch Pfadgelegenheits-Bewertung wird eine Infrastruktur zur Pfadgelegenheit.

Direkt unter der Pfadentscheidung sehen wir „System 2“ (Kahneman) mit der „Aufmerksamkeit“ in der Mitte. Links filtern semantische Pfadgelegenheiten die „Eindrücke“, die auf den „Körper“ treffen in „Unterscheidungen“. Smeantische Pfadgelegenheiten ermöglichen dazu nicht nur Sprechen/Schreiben/Denken, sondern erlauben auch erst den Zugriff der Aufmerksamkeit auf viele materielle Pfadgelegenheiten, denn das „System 2“ kann nur über semantische Unterscheidungen auf Pfadgelegenheiten zugreifen.

Der „Plan“ trennt (ungefähr) „System 1“ und „System 2“, wobei die Motivation zwar hauptsächlich in System 1 angesiedelt ist, aber in System 2 hineinragt. Das System 1 ist gewissermaßen das „Unbewusste“, hier passiert das Unwillkürliche, wie „Erwartungen“ und „Reaktionen“.

Die divudelle Perspektive ist zweifach „gerounded“, durch den „Ort“ und die „Emotion“, wobei die Emotion teil aller Pfadgelegenheiten ist, die sie mit der emotionalen Q-Function Bewertungen auflädt, einer Art emotionale Vorbewertung für die planende Q-Function des System 2.

V.l.n.r.: Links strömen die Eindrücke der Welt auf den Körper und damit die Perspektive. „Der Blick des Anderen“ wacht über die Pfadentscheidungen , eindrücke auf den Körper und unten wird nochmal darauf hingewiesen, dass die semantischen Pfadgelegenheiten des Dividuums in Wirklichkeit immer die Sprache des Anderen sind.

Auf der linken Seite der Perspektive sehen wir so grob den „sensorischen Apparat“ des Dividuums, während wir auf der rechten Seite grob den motorischen Apparat des Dividuums sehen, wobei diese Trennung in Wirklichkeit ebenso schwer aufrecht zu halten ist, wie Trennung zwischen „materieller“ und „semantischer“ Pfadgelegenheit.

Ganz rechts ist die Pfadgelegenheits-Turing-Maschine und ihr Infrastruktur-Band abgetragen und die beiden Pfeilbögen symbolisieren die Operationen der Turing-Maschine. Unten finden sich die „Infrastrukturen des Anderen“ (die wir ständig nutzen) und oben die „Barrieren des Anderen“ (die uns ständig unsere Pfadgelegenheiten vereiteln).

Hier wie es läuft: Eine Pfadgelegenheit wandert vom Plan in die Aufmerksamkeit, findet in der Pfadentscheidung ihre Umwandlung in Pfadgelegenheit und Geschichte und wandert in die pfadabhängige Infrastruktur.

1. Ort. Erstmal bedeutet Perspektive die Einsicht, dass wir alle „von einem konkreten Ort“ aus sehen, denken, handeln und sprechen. Ich hab das von Donna Haraway und klar, die Einsicht ansich ist erstmal nichts Neues und das behauptet Haraway auch nicht, aber sie macht etwas Neues daraus: eine Übung.

In Krasse Links No 10 führe ich Donna Haraway so ein:

Das Werk ist zunächst nicht so leicht zugänglich, nicht, weil sie so voraussetzungsreich schreibt, sondern weil man erst eine Menge verlernen muss, bevor alles Sinn ergibt. Ihr wichtigster Beitrag in der Philosophie ist weniger eine ausgefeilte Theorie der Welt, als vielmehr ein bestimmer Blick. Ich habe das letzte Jahr damit verbracht, diesen Blick einzuüben und wenn man das schafft, dann eröffnet sich im wirren, mäandernden und eklektischen Werk Haraways plötzlich ein Füllhorn von Sinn.

Haraway denkt – mehr noch als Bruno Latour – aus dem Netzwerk heraus. Dass klingt banal, aber es ist wirklich nicht einfach. Eine erste, überraschende Lektion ist zum Beispiel, dass Du als Netzwerkteilnehmer das Netzwerk selbst nie zu Gesicht bekommst. Das heißt, du verlierst erstmal eine ganz bestimmte Sicht, nämlich die Draufsicht. Also jene Illusion von ort- und körperlosem Schweben über den Dingen, die gerade in der abendländischen Tradition einen Großteil des wissenschaftlichen Blicks ausmacht. Diese Perspektive, so Haraway, sei nicht real, sondern reine Imagination. Eine männliche Machtphantasie.

Haraway zu denken, bedeutet erst einmal ein Loslassen dieser Perspektive und die eigene Situiertheit in der Welt anzuerkennen und damit auch die Tatsache, dass jedes Denken immer unter ganz bestimmten materiellen Verhältnissen und an einem ganz bestimmten Ort in der Semantik stattfindet. Es ist, als müssten sich die Augen erst an die veränderten Lichtverhältnisse anpassen, aber langsam schärft sich mein Blick auf Beziehungsnetzwerke: auf materielle Abhängigkeiten, genauso wie auf Semantiken.

Eine andere Sache, die passiert, wenn man anfängt die Netzwerkperspektive ernst zu nehmen, ist, dass alles unrein wird. Es gibt plötzlich keine saubere Kategorien mehr, weil alles in einander hineinragt. Das gilt vor allem für das Selbst. Das Selbst steht nicht mehr als abgeschiedene Entität den Dingen gegenüber, sondern interferiert durch seine Eingebundenheit mit den Semantiken und Abhängigkeiten der Umwelt.

Ort ist der Referenzpunkt von allem. Nichts ist einfach gegeben, alles ist teil der Welt, auch und vor allem, deine Perspektive.

2. Eindrücke: Im Gegensatz zum Individuum hat das Dividuum keinen Körper, aber es ist zu relevanten Teilen ein Körper. Der Körper ist die wichtigste Infrastruktur des Dividuums und netzwerkzentral zur Navigation aller anderen Infrastrukturen und damit die wichtigste aller Pfadabhängigkeiten (oh gott, wie ich gerade gar nicht danach lebe …).

Der Körper ist aber auch auf eine andere Art, teil der Perspektive. Achtet mal drauf, wie allein ein leichtes Hungergefühl oder eine unterschwellige Hornyness eure Sicht auf die Welt strukturiert.

Auch sonst drückt sich die Welt auf vielfältigste Art und Weise in das Dividuum ein und verändert seine Perspektive auf die Welt, auch dann, wenn wir es nicht gut benennen können. Unser Vokabular ist begrenzt und ständig kommen neue Einflüsse hinzu, für die wir noch keine Begriffe haben. Unser Vokabular reicht meist nur für die direkt physische „Objekt-Welt“, die wir um uns herum kreiert haben, aber die Versuche, die Strukturen, in die wir eingebunden sind, zu beschreiben, haben noch viel aufzuholen. Uns fehlt zum Beispiel die Sprache, die vielen Vektoren der strukturellen Gewalt zu benennen und zu beschreiben, denen wir zunehmend, aber sprachlos ausgesetzt sind.

3. Materielle Pfadgelegenheiten. Die Pfade, die wir in die Unterscheidungen unserer Eindrücke zu erkennen glauben. Dazu gibt es einen eigenen ausführlichen Explainer.

4. Semantische Pfadgelegenheiten. Die Pfade, die wir in den gemeinsamen Erwartungen mit dem Anderen zu erkennen glauben. Das Feld der semantischen Pfadgelenheiten liefert aber auch die Unterscheidungen und ihre semantischen Relationen, mit denen wir unsere Welt deuten und entlang derer wir unsere Aufmerksamkeit justieren. Die Erwartungserwartungen der Gesellschaft sind die Art, wie wir die Welt „formen“ und entscheidet daher, was wir als „Information“ wahrnehmen und was nicht. Die semantischen Pfadgelegenheiten sind deswegen kritisch, denn sie liefern unter anderem auch die heuristischen Schablonen, mit denen wir in der Welt nach Pfadgelegenheiten Ausschau halten.

Und hier ist der schwierige Part, den es zu verstehen gilt: Dividuen sehen unterschiedliche Pfadgelegenheiten in derselben Welt, je nach dem wo und wie sie aufgewachsen sind, welche Pfade ihnen vertraut sind, welche Erzählungen sie gehört haben und welchen sie glauben, wie sie sich selbst erzählen und welche Ziele sie sich setzen, usw. Das heißt, Zugang zu Bildung hat Ripple Effects durch das ganze Leben.

Der Instragrammer Michael Metz veranschaulicht das hier schön anhand von Reverse-Engeneering eines Karriere-Pfads.

5. Plan. Alle Dividuen planen. Pläne sind imaginierte Pfad im Netzwerk der Pfadgelegenheiten eines Dividuums zu einem Ziel. Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die einfach Dinge tun können, sondern sequenzielle Pfadwesen, die immer nur einen Schritt nach dem anderen tun können, brauchen wir sogar fürs „aufs Klo gehen“ einen Plan. Und obwohl wir zwar immer nur einen Schritt nach dem anderen tun können, können wir trotzdem mehrere Pläne gleichzeitig verfolgen und uns was zum Lesen mitnehmen. Pläne sind unsere Multithreading-Architektur.

In Krasse Links No 31 habe ich über Agency und Pfadgelegenheiten, aber auch die Rolle von Plänen geschrieben.

Das, was Joscha Agency nennt und sie der Intelligenz des „Agents“ zuschreibt, nennt die Cyborg Freiheit. Konkreter: horizontale Freiheit, bzw. Positive Freiheit. Man könnte sie auch relational-materielle Agency nennen.

Unsere Freiheit ist der Ausschnitt, der uns zugänglichen Pfade im Netzwerk der Pfadgelegenheiten.

Unsere Freiheit ist diskret, also abzählbar. Sie existiert nur in konkreten, materiellen Pfadgelegenheiten, die uns zu einem Zeitpunkt x zur Verfügung stehen: der Wasserhahn, das Stück Straße zum Weg auf die Arbeit, das Stellenangebot in der Zeitung, das Essen im Restaurant, das Wort auf der Zunge. Die Pfade, auf die die Pfadgelgenheiten führen sind ungewiss, aber das heißt nicht, dass wir ziel- und planlos sind.

Ziele sind Netzwerkzentralitäten im Netzwerk der Erzählungen. Wir sind immer auf Mission als Maincharakter in den vielen Geschichten, die wir uns über uns selbst erzählen und die steuern alle auf ein Happyend?

Pläne sind imaginierte Pfade im Netz der Pfadgelegenheiten auf dem Weg zum Happyend. Mal mehr mal weniger konkret, mal mehr oder weniger realistisch, etc. Damit ein Plan glückt, müssen Pfadgelegenheiten teils hart erarbeitet werden und manche Pfadgelegenheiten kann man nur erhoffen. Wenn die Ungewissheit zu groß wird, muss man Pläne auch beerdigen und das ist immer schmerzhaft.

Das Netz der Pfadgelegenheiten hat ebenfalls Netzwerkzentralitäten und die nennen wir „Liquidität“. Geld ist nicht der einzige, aber netzwerkzentralste Hub in diesem Netzwerk, zumindest im Kapitalismus.

Damit können wir schon mal drei Freiheiten ausmappen:

Die nominelle Freiheit ist die Anzahl, Vielfalt und Qualität der Pfadgelegenheiten, die von einem Dividuum zum Zeitpunkt X ausgehen und deren Länge durch das Geld als Radius begrenzt wird. Die nominelle Freiheit ist also der Ausschnitt im Netz der Pfadgelegenheiten, der für das Dividuum zum Zeitpunkt X zugänglich ist. Es ist nur eine theoretische Freiheit, weil sich niemand die Arbeit machen würde, diese Pfade auszukartographieren.

Die plausible Freiheit ist das viel kleinere Subset dieser Pfade, die dem Dividuum tatsächlich als „plausibel“ im Bewusstsein schwirren. Sie wird somit einerseits durch die nominelle Freiheit begrenzt, aber auch durch die dem Dividuum zugänglichen Erzählungen. Diese plausiblen Pfade sind natürlich imaginiert und auch hier gilt: sie sind nicht rigoros ausgemappt und schon gar nicht vollständig und oft auch gar nicht wirklich plausibel, wenn man genau hinsieht, aber sie bilden das Freiheits-Hintergrundrauschen, vor dessen Kulisse jede Pfadentscheidung getroffen wird. Sie ist der Raum, in dem wir planen und entscheiden. D.h. jede Pfadentscheidung ist immer eine Entscheidung gegen andere plausible Pfade in diesem Raum.

Die geplante Freiheit ist die Freiheit, die wir im Alltag spüren. Hier ist die Schmerzempfindlichkeit am größten. Geplante Freiheit ist die Leichtigkeit (oder nicht), mit der wir unseren Plänen nachgehen. Nichts vermittelt so sehr das Gefühl von Unfreiheit, als wenn Barrieren unsere Pläne verhageln.

Horizontale Macht (auch hegemoniale Infrastrukturmacht) begrenzt unsere nominelle und damit die horizontale Freiheit. Als Pfadopportunist*innen nehmen wir diese Form der Macht nicht als Gewalt wahr, weil die vorenthaltene Agency nie erwartet wurde. Wir fügen uns.

Vertikale Freiheit (auch negative Freiheit) ist geplante Freiheit. Vertikale Macht (auch souveräne Infrastrukturmacht), also Gewalt, kann sich jederzeit zur Netzwerkzentralität in den Pfadabhängigkeiten Deiner Pläne machen und macht Dich somit extrem abhängig. Freiheit von dieser Form der Abhängigkeit ist die Freiheit, planen zu können.

Und dann gibt es noch die semantische Macht (auch hegemoniale Semantikmacht), die die plausible Freiheit … zumindest mitgestaltet. Wer erzählt die Geschichten, die umherschwirren, an denen auch wir unsere Lebenspfade, also Pläne orientieren?

Was auch spannend wäre: „Chancengleichheit“ aus Cyborgsicht einmal auszubuchstabieren.

Im Pfadgelegenheits-Explainer erkläre ich Pläne so:

Aber hier ist das Problem: Im Moment der Pfadentscheidung ist es unmöglich vorherzusehen, wohin einen eine Pfadgelegenheit bringt und oft wird alles ganz anders, als wir es uns vorgestellt haben. Deswegen machen wir Pläne und starten „Projekte“, aber weil nie etwas nach Plan verläuft, leben wir in den Ruinen unserer Pläne, aber vor allem in den Ruinen der Pläne anderer.

6. Pfadabhängigkeiten Wenn man in einen Raum reingegangen ist, ist es nützlich, sich zu merken, wie man wieder rauskommt. Und wenn man durch ein Haus mit vielen Räumen geht, muss man sich viele Pfadabhängigkeiten merken. Hier unterscheiden sich Individuum und Dividuum auf den ersten Blick nicht, aber das Dividuum hat dem Individuum dennoch etwas voraus: Es hat eine infrastrukturbewusste Sprache, die die Eigenheiten und Vertraktheiten von Pfadabhängigkeiten einpreist.

Beispiel: Nehme ich eine Pfadgelegenheit und gehe den Pfad weiter und immer weiter, dann erhöht sich dadurch automatisch meine Abhängigkeit von der ursprünglichen genommenen Pfadgelegenheit. Das stimmt sowohl für das Umherirren im Wald, für das Coden von komplexen Programmen, für die Struktur eines Textes beim Schreiben, als auch für das Business, das seinen Vertriebskanal vor 5 Jahren voll auf Amazon Marketplace umgestellt hat.

Wir spüren diese Abhängigkeit durchaus und wir blicken auf Abhängigkeiten nicht selten mit bangem Blick, aber uns fehlt die Sprache, die die Gefahr „plastisch“ machen würde. Wir sind doch freie Individuen, versichern wir uns. Und wenn die Schmerzen zu groß werden, wird „der Markt uns schon auffangen“. Das Individuum ist immer auch eine Verdrängungserzählung.

Deswegen produziert die Gesellschaft vielfältige und enthusiastische Erzählungen über plausible und begehrenswerte Pfadgelegenheiten, aber hat keine angemessene Sprache gefunden, die sich aus den Pfadgelegenen ergebenden Pfadabhängigkeiten zu beschreiben. Wir sprechen über „das Klima“ als sei es ein Objekt, wie eine aussterbende Tierart, die nur ein paar Ökospinner beweinen würden und als ginge es nicht um ein grundlegendes infrastrukturelles Problem mit einer tiefsitzenden Pfadabhängigkeit für alles, was wir tun und sind.

Das wir dafür keine Sprache gefunden haben, liegt nicht an unserer mangelnden „Intelligenz“, sondern weil wir pfadabhängig vom Individuum denken und sprechen.

Die Infrastrukturvergessenheit des Individuums ist sein Geburtsfehler. Es entwirft sich als von der Welt losgelöster, autonom handelnder Agent, dessen Pfadgelegenheiten immer schon da waren, und das immer schon schlau war, praktisch seit Geburt, wobei es das eigene „Geborensein“, wie auch die Sterblichkeit, meist erst auf zweifache Nachfrage zugibt.

In Krasse Links No 55 beschreibe ich die Kopfgeburt des Individuums so:

Descartes kleiner Trick war, einfach so zu tun, als gäbe es die Sprache nicht – also diese externe Infrastruktur, mit der er seine Gedanken organisiert und ohne die er nichts wüsste vom „Ich“, vom „Denken“ und vom „Sein“. Das ermöglicht ihm, sein Denken („Res Cogitans“) von „dem Außen“ („Res Extensa“) abzutrennen und damit den Widerspruch von Geist (Vernunft/Intellekt) und Welt zu behaupten.

Dadurch wurde auch die Illusion des infrastrukturfreien Sehens möglich, der Blick von nirgendwo, der objektive Blick, der – wie wir alle wissen – der einzig vernünftige Blick ist.

Der Descartes-Trick funktioniert für alle Infrastruktur, denn genau betrachtet ist nicht nur unser Denken, sondern auch unser Handeln immer infrastrukturvermittelt. Wir können nicht denken oder tun, was wir wollen – nicht mal wollen, was wir wollen – denn wir sind immer an einem ganz konkreten Punkt in der Welt mit ganz konkreten, materiellen und semantischen Pfadgelegenheiten, die uns zu einem konkreten Zeitpunkt zur Verfügung stehen.

Aber indem wir die Infrastruktur verdrängen (jedenfalls bis sie kaputt geht), können wir uns die Agency selbst zuschreiben. Unserem individuellen Ich können wir dadurch „Fleiß“, „Intelligenz“, „Geschmack“ und „Freiheit“ attestieren, ganz besonders wenn wir mit 200 Sachen auf der Autobahn an den Losern vorbeirasen.

Diese Selbstzuschreibung von Agency war nützlich, unter anderem im Kolonialismus, wo man die eigenen Infrastrukturen erfolgreich gegen andere Völker wendete. Die Genozide wurden schon damals mit der eigenen „Zivilisiertheit“ gerechtfertigt und der nun mal überlegenen europäischen „Vernunft“, was aber eigentlich nur meinte: infrastrukturvermittelte Agency. Aus dieser Erlaubnisstruktur ergibt sich der Koloniale Blick: eine implizite Hierarchie der Völker entlang ihres „Entwicklungsgrades“, die bis heute in allen unseren Debatten spukt.

Das Individuum ist auch Grundlage unseres Blicks auf die eigene Gesellschaft. Statt Menschen zu sehen, die jeweils versuchen, in den ihnen zur Verfügung stehenden Infrastrukturen zu überleben, haben wir die Gesellschaft als „Markt der Individuen“ imaginiert, in der dein Platz in der Welt, deiner „individuellen Leistung“ und damit über Bande auch deiner „Intelligenz“ entspricht.

Wenn Du den goldenen Löffel im Mund für eine Ausbildung an einer Elite-Universität eingetauscht und mit dem erworbenen Wissen und den Kontakten von Papa ein erfolgreiches Start-Up gegründet hast, dann bist Du „deines Glückes Schmied“. Wenn du in Gaza aufgewachsen bist, in der dritten Generation vertrieben in den Ruinen Deines Hauses sitzt und Israel am liebsten abschaffen willst, bist du ein Antisemit und kannst weg.

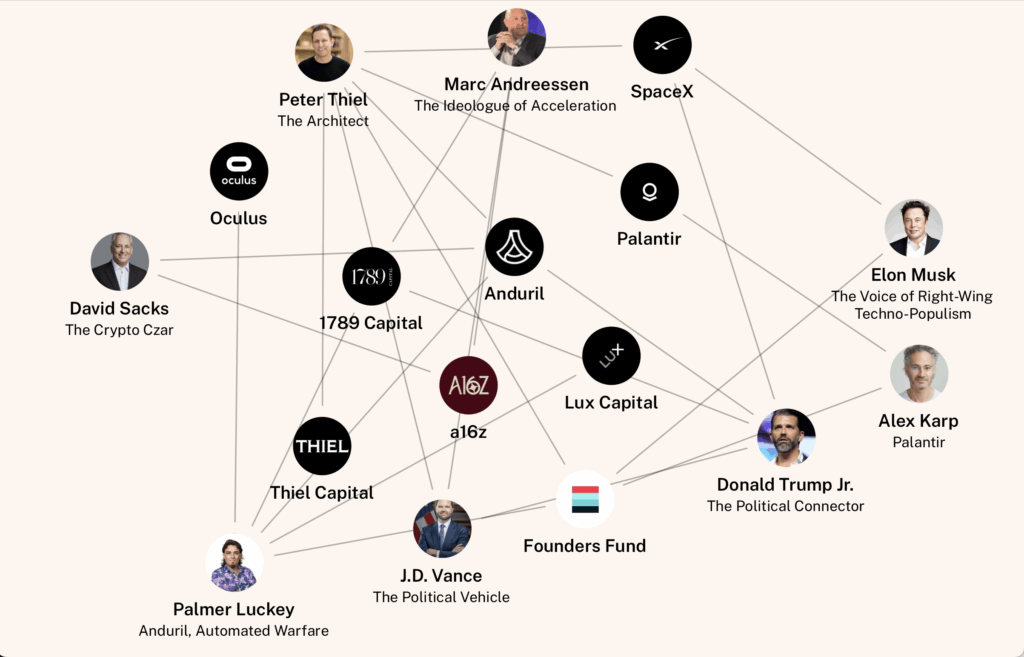

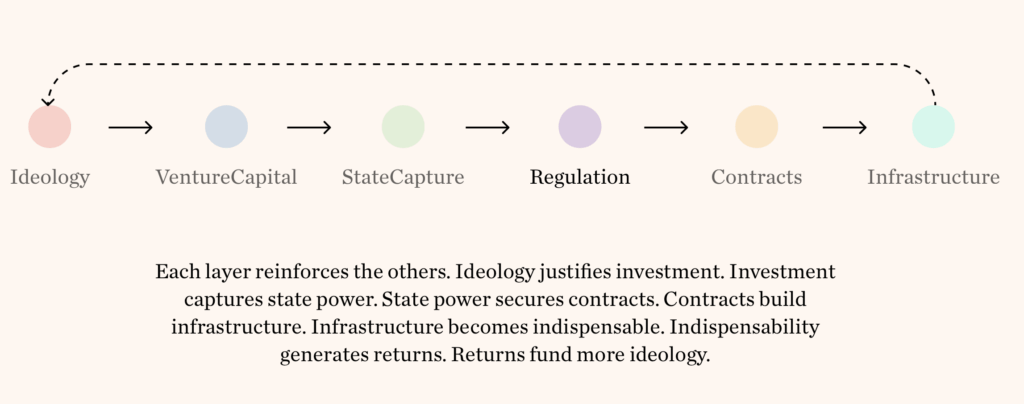

Wie gesagt, das ist alles logisch und richtig so und dass die Super-Individuuen aus dem Silicon Valley mit ihren milliardenschweren aber völlig verdrängten Infrastrukturen gerade die Demokratie abräumen, liegt nicht daran, dass sie an ihrer eigenen Super-Individualität durchgeknallt sind, sondern das ist ein wichtiger Schritt zur nächsten Stufe menschlicher Zivilisation: AGI – die Vernunft in der Flasche. Das letzte Individuum.

Ich hänge immer alles so der an Descartes auf, aber natürlich weiß ich, dass die Geschichte komplexer ist, aber auch lustiger. Das Individuum entstand eigentlich als „Juristische Person“ im späten Mittelalter. Eine „legale Fiktion“ einer „Annahme von Urteilskraft“ und „freien Willen“, die die Pfadgelegenheit des „rechtskräftigen Vertrags“ ermöglichte, dazu eine Art Eigentumsrecht an sich selbst, bzw. seinen Körper (hence: Marx‘ doppelte Freiheit des Arbeiters). Ja, die Karriere des Individuums begann als infrastruktureller Ur-Grundbaustein, der sich bildenden kapitalistischen Ordnung. Descartes ist auch nur ein Dividuum, das als Jurist den Vibe seiner Zeit eben durch die Paragraphen der Gesetzbücher aufschnappte und restrukturierte.

Aber Descartes liefert mit seiner „Cartesianischen Meditation“ nicht nur die philosophische Erlaubnisstruktur des „Individuums“ und damit der Grundlage des kapitalistischen Systems, sondern ahmt dabei gleichzeitig die Geste vor, die ihm immer mehr Dividuen nachmachen sollten, im Versuch, Individuum zu werden. Er verleugnete seine Eingebundenheit in die Welt, indem er seine geerbte und über einen langen Prozess eingeübte Unterscheidungs-Infrastruktur einfach seinem eigenen „Res Cogitans“ zuschrieb, um eine Abgeschlossenheit zu behaupten, die nicht existiert. (Nebenbei ist das auch der ursprüngliche „geistige Diebstahl“, auf dem der geistige Diebstahl des „Urheberrechts“ basiert, aber das führt hier zu weit.)

Infrastrukturvergessenheit ist seitdem bei uns eine anerzogene Haltung, die pfadabhängiger Teil eines implizit herrschaftlichen Blicks auf die Welt ist. Descartes Unterscheidung von „Res Cogitans“ und „Res Extensa“ war rückblickend eine verheerende Pfadentscheidung im westlichen Denken, die uns allen die Sicht auf die Gesellschaft verstellt und die uns gerade in Form der Broligarchie und ihrem Gefasel von „AGI“ um die Ohren fliegt.

„Frühe Pfadentscheidungen strukturieren die späteren vor“, das ist nichts Neues, tausendfach erlebt, tausendfach beschrieben und das ist ja wirklich auch kein Hexenwerk, das zu verstehen, sogar als Individuum.

Aber es wichtig zu finden, es als relevanten Vektor bei den Beobachtungen der Welt mitlaufen zu lassen, und zur Grundlage eigener Entscheidungen zu machen, ist etwas, das dem Individuum schon aus seiner Selbsterzählung heraus schwer fällt. Das Individuum redet nicht gerne über Abhängigkeiten.

Ich behaupte: das fällt dem Dividuum leichter, allein schon weil das Wort „Pfadgelegenheit“ jeder sogenannten „Handlung“ die Bürde des Pfades aufzwingt. Wenn jede meiner Entscheidung Teil eines Pfades ist, dann passiert keine Handlung ohne Vorgeschichte und, noch wichtiger, keine Handlung bleibt ohne Konsequenzen.

Und fängt man an, sich und seine Welt so zu erzählen, also anders zu sehen, mit andern Unterscheidungen, dann bekommt man mit der Zeit ein Orientierungswissen aus differenzierten und zu Erwartungen geronnenen Erfahrungen. Ein „Gefühl“ für Dimensionen, Dynamiken, Flüssen und Kritikalitäten in den Pfadabhängigkeiten unseres gemeinsamen Seins. Wobei das andere „Sehen“ nicht wirklich ein kognitives „Aufnehmen“ oder „Verstehen“ ist, sondern eine Art zusätzlicher, im idealfall mit eigenen Schmerzerfahrung beschwerter „Sensor“ für die Welt, der der Perspektive „im Netzwerk Sein„, als zusätzliche Dimension hinzufügt und Semantiken wie „Techfaschismus“ und „Klimakatastrophe“ zu emotional-plastischen Ungetümen aus antizipiertem Schmerz inszeniert. Ist nicht schön, tbh.

7. Die Erwartungen der anderen/des Anderen. Natürlich haben ständig Menschen um uns herum Erwartungen an uns und einen nicht geringen Teil unserer Zeit, verbringen wir damit, Erwartungen anderer gerecht zu werden.

Aber die Erwartungen der anderen modifizieren unsere Perspektive auch auf andere Art. Ludwig Wittgenstein kam bei seinem Nachdenken über Sprache letztlich zu zwei wichtigen Schlüssen: Wofür wir keine Semantiken haben, darüber können wir nicht sprechen. Und die Einsicht, dass es keine Privatsprache geben kann. Sprache können wir nur gemeinsam erschaffen.

Der Grund dafür – und Wittgenstein ist da sehr explizit – ist, weil wir uns selbst keine Gesetze auferlegen können. Also wir können das schon versuchen, so Wittgenstein, aber wir brauchen eine externe Instanz, die uns materiell Grenzen setzt. Die materiell „Nein“ zu uns sagt. Im Grunde hat Wittgenstein das Dividuum entdeckt.

Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die „autonom“, also Selbstgesetzgebend sind, sondern Dividuen, die sich gegenseitig outcallen, führen wir beim Handeln und Sprechen immer den Blick des Anderen bei uns, wie einen Passierschein.

Der Blick des Anderen wurde oft „Gewissen“ genannt, bei Sigmund Freud ist es das „Überich“ und in meinem Newsletter verweise ich auf den Blick des anderen meist als Erlaubnisstruktur.

Wie das Dividuum diesen Blick des Anderen konstruiert, ist natürlich sehr unterschiedlich. Für manche ist es vor allem nach wie vor Gott, für manche mehr der strenge Vater, für andere Romanfiguren, aber ich denke heute in unserer modernen Welt ist dieser „Blick des Anderen“ meist ein wilder Mix aus sich überlagernden Perspektiven unterschiedlicher Communities, Autoritäten, Freundschaften und sonstigen Loyalitäten. Ein aggregierter Blick all derer, denen man sich verpflichtet fühlt.

Unsere Erlaubnisstrukturen sind natürlich verkoppelt mit den Pfadabhängigkeiten, denn die Erwartungen derjenigen, von denen wir abhängig sind, können wir nicht ignorieren. Deswegen konzentriert Macht immer auch Aufmerksamkeit.

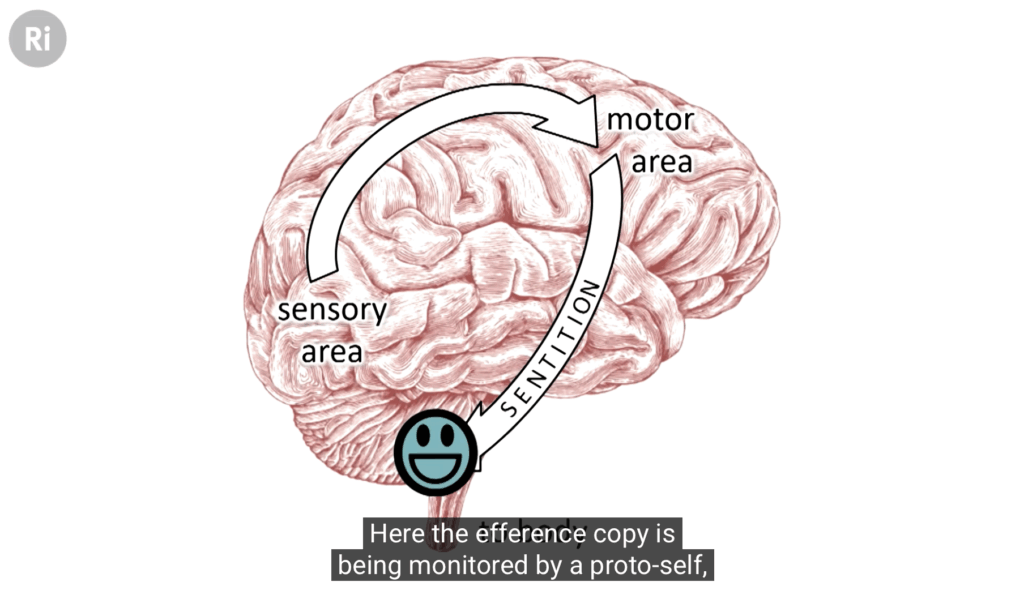

8. Emotion/Empathie. In Krasse Links No 74 kam ich mit Hilfe des Biologen Nicholas Humphrey darauf, wie Pfadgelegenheit und Emotion zusammenhängen:

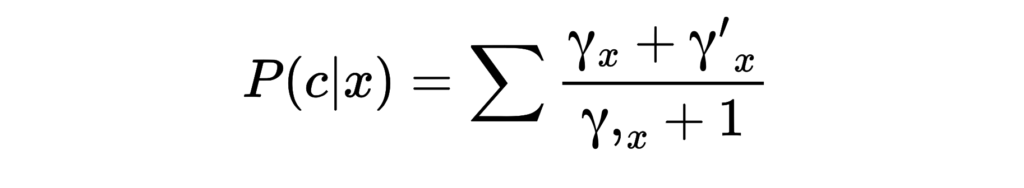

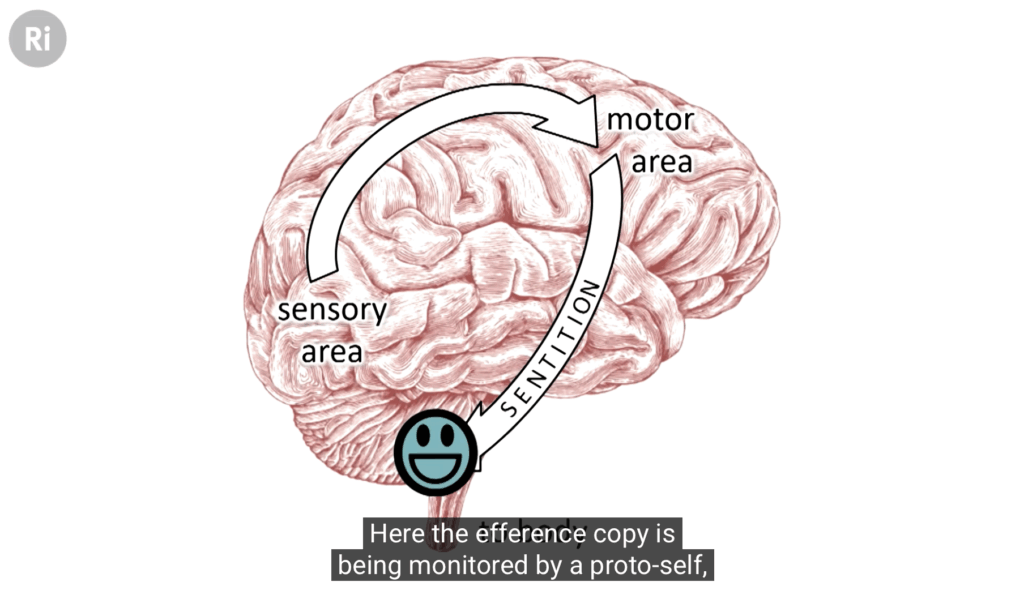

Ich bin seit ungefähr anderthalb Jahren fasziniert von der evolutionären Theorie des Bewusstseins, die der Biologie Nicholas Humphrey aufgestellt hat. Hier sein absolut sehenswerter Vortrag zum Thema, sein letztes Buch muss ich aber noch lesen.

Der ganze Vortrag ist erhellend, aber ich bin vor allem auf seiner evolutionsbiologischen Spekulation über die Entstehung von Perzeption und Bewusstsein hängengeblieben.

Versetzen wir uns in eine Amöbe zur Halbzeit der Evolution.

- Die Amöbe entwickelt unterschiedliche Reaktionen auf Reizungen durch unterschiedliche Umweltzustände: Sie unterscheidet, sagen wir „Grenze“ (hier gehts nicht weiter), „Gefahr“ (run), „Lecker“ (absorbieren).

- In Phase 2 bildet die Amöbe eine Art Proto-Gehirn, ein Zentrum, das die Umwelt-Reaktionen zentral koordiniert.

- Dann die entscheidende Phase: Von den Reaktionensmustern werden „Kopien“ angelegt und im Zentrum abgelegt und nervlich adressierbar gemacht. Humphrey meint, dass „Planung“ und komplexeres verhalten damit möglich wird.

- Zuletzt: Feedbackloop zwischen motorischem System, sensorischen System und den gespeicherten Repräsentationen, ermöglicht/unterstützt durch die Evolution zu Warmbutkörpern.

Soviel zu Humphrey, aber hier, was mein von der Metaphysik des Dividuums „bamboozeltes“ „Mind“ daraus macht:

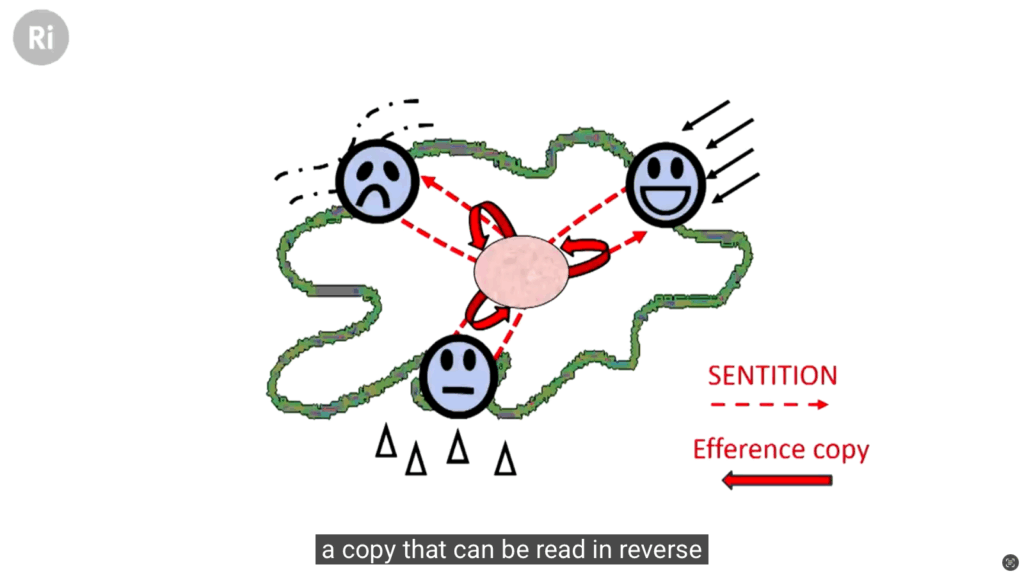

Dieser evolutionäre Moment, den Humphrey beschreibt, ist gleichzeitig die Geburt der „Pfadgelegenheit“, sowie von Emotion, Semantik, von Handlung, von Widerstand und von Kunst.

Aber Eins nach dem Anderen:

- Mit der Kopie des Reizreaktionsschemas zum repräsentativen Aufrufen in Schritt 3 haben wir das, was ich im Pfadgelegenheits-Explainer eine „projizierte Handlung“ nenne.

- Und in Schritt vier sehen wir, wie die Pfadgelegenheits-Turing-Machine angeworfen wird: Infrastruktur (das motorische System in seiner Umwelt), Perspektive (das sensorische System) und die Reizreaktionsschema-Kopie „projizierte Handlung“ sind beisammen.

- Erste Pfadabhängigkeit: Erst durch die „projizierten Handlung“ kann es „Handlung“ überhaupt geben. Erst wenn ich einen Pfad projizieren kann, kann ich mich für ihn entscheiden. Alles andere ist nur „Reaktion“.

- Pfadabhängigkeit der Pfadabhängigkeit: Entscheidung aber gibt es erst, wenn ich eine Wahl habe. Eine Wahl habe ich aber nur, wenn ich mehrere Pfadgelegenheiten zur Auswahl habe, klar, aber um auswählen zu können, muss ich erst in der Lage sein, eine Pfadgelegenheit zu antizipieren, ohne sie nehmen zu müssen. Freiheit entsteht aus dem „Nein“.

- Pfadabhängigkeit der Pfadabhängigkeit der Pfadabhängigkeit: „Antizpieren“ (Q-Function) heißt aber konkret, eine Reaktion zu projizieren, das heißt, zu imaginieren. So tun als ob. Jede Pfadgelegenheit ist eine Inszenierung.

- Pfadabhängigkeit der Pfadabhängigkeit der Pfadabhängigkeit der Pfadabhängigkeit: Das kopierte Reiz-Reaktionsschema ist nicht nur Q-Function, sondern auch eine Proto-Emotion. Das heißt: Pfadgelegenheiten sind immer und grundsätzlich mit Emotionen verbunden. Der Schmerz des Hungers (Reproduktionsschmerz), aber auch der Genuss des Essens, der Schmerz der nicht (mehr) vorhandenen Pfadgelegenheiten (Netzwerkschmerz) und der Genuss des Flows, die vielen unterschiedlichen Schmerzen der Gefahr (Stress) und der Genuss der Geborgenheit sind von vornherein Teil der kopierten Reaktionsmuster, also auch unserer „projizierten Handlungen“ und immer wenn ich etwas entscheide, spielt ein komplexes Zusammenspiel dieser Emotionen eine Rolle (Bauchgefühl).

- Mit der Pfadgelegenheit entsteht also auch „Agency“ und wir verstehen: Die Bedingung der Möglichkeit von Freiheit ist die Fähigkeit einen emotionalen Pfad zu inszenieren und dann „Nein“ zu ihm zu sagen.

Emotion ist inszenierter Reiz und sie ist gleichzeitig die Proto-Semantik, von der alle Semantik stammt. Und das heißt, das alles, was wir tun, alles, was wir sagen, nicht nur durch unseren Ort, sondern auch durch Emotion „gegrounded“ ist. Und weil aber Emotion immer schon eine Inszenierung, d.h. eine Iteration als Wiederholung in der Differenz ist, ist sie immer schon semantisch. Deswegen reicht es, Körperhaltungen, oder die Angst in Gesichtern zu sehen, um Schmerzen in uns auszulösen. Empathie bedeutet, den Schmerz oder den Genuss des Anderen in uns selbst inszenieren.

Die jeweilige emotionale Groundingslandschaft ist natürlich dividuell extrem verschieden, denn wir alle haben unterschiedliche Schmerz- und Genusserfahrungen gemacht, die uns unterschiedlich fähig machen, sich mit dem Schmerz anderer zu verbinden. Und je nachdem, in welcher emotionalen Groundings-Landschaft man lebt, verändert das die Perspektive auf die Welt durch den „Klang“ aller Unterscheidungen.

Das Wort „Krieg“ klingt in den Ohren von jemandem, der in einem lebt, anders, als in meinem und das Wort „Klimakatastrophe“ klingt nicht so, wie es klingen sollte, wie ich mal in Krasse Links No 29 feststellte.

Mein Doktorvater Bernhard Pörksen sagte mal zu mir: „Realität ist das, was noch da ist, wenn du nicht dran glaubst“, was ich auf Anhieb schlüssig fand. Aber wenn man das zu Ende denkt, bedeutet das: Realität ist Schmerz. Schwerkraft ist nicht „wahr“, weil Newtons Formeln stimmen, sondern weil hinfallen weh tut.

Schmerz ist auch der Antrieb für diesen Newsletter. Ich habe mir am Netzwerk den Kopf gestoßen und seitdem verarbeite ich diese Erfahrung zu einer anderen Sicht auf die Welt.

Der Klimawandel ist wie das Netzwerk ein Hyperobjekt, und meine These zu Hyperobjekten ist, dass sie Dimensionen von Realität sind, zu denen uns noch der passende Schmerz fehlt. Deswegen hat dieser Clip wahrscheinlich mehr zum allgemeinen Verständnis des Klimawandels beigetragen als der letzte IPCC-Bericht.

Abstrakte Semantiken ohne Schmerz sind Hyperobjekte. Wir können sie „intellektuell“ verstehen, aber wir fühlen sie nicht und deswegen fällt es uns schwer, sie zu fürchten. Das wissen um Gefahren bleibt leicht wie eine Feder und die Sorge darum optional.

Semantiken wie „Faschismus“ sind auch abstrakt, aber das (integenerationale) Trauma der tatsächlichen Faschismus-Iterationen klingt körperlich mit. „Faschismus“ ist ein schwerer Begriff.

In die Unerträgliche Leichtigkeit des Seins formulierte Milan Kundera den Zusammenhang so:

Schwere, Notwendigkeit und Wert sind drei eng zusammenhängende Begriffe: nur das Notwendige ist schwer, nur was wiegt, hat Wert

9. Aufmerksamkeit. Jedes Dividuum hat nur eine begrenzte Aufmerksamkeit und das bedeutet, dass jede Perspektive gleichzeitig ein Fokus ist, der anderes Ausschließt.

Die Perspektive beginnt mit der Unterscheidung und die Unterscheidung ist gleichzeitig die Fokussetzung auf eine der Seiten, der Unterscheidung. Aufmerksamkeit ist das zeitliche Grounding der Perspektive.

Jede Pfadgelegenheit erfordert ein gewisses Maß an Aufmerksamkeit, auch wenn uns mit der Zeit viele Dinge in „Fleisch und Blut“ übergehen. Viele Tätigkeiten, spezielle wiederkehrende Tasks werden durch Übung „naturalisiert“, so dass sie ohne eigens mobilisierten Planungsaufwand durchgeführt werden können.

Aufmerksamkeit plus Planung ist gewisser maßen der „System 2“-Mode von Daniel Kahnemann, aber viel bescheidener: als der Fokus auf die aktuell relevanten Unterscheidungen einer Perspektive, im Kontext eines Pfads.

Aufmerksamkeit ist knapp und überall gefragt: Ein Gutteil ihres Lohns bekommen produktiv Arbeitende für ihre Aufmerksamkeit. Die Werbeindustrie hat aus Aufmerksamkeit ein Trillion-Dollar Business gemacht. Aufmerksamkeit ist eine Währung. In Krasse Links No 38 schrieb ich:

Das Paper, das den Transformeransatz, der heute alle generativen KIs antreibt, der Welt vorstellte, hieß literally: „Attention is All you need“ und das denke ich mir auch immer wieder, wenn ich meinen Hund streichel. Der körperlichen Kontakt ist wichtig, doch das Streicheln ist nur Medium einer noch wichtigere Ressource: Aufmerksamkeit.

Dass Aufmerksamkeit eine knappe Ressource ist, um die ein ökonomischer Kampf geführt wird, hatte bereits Georg Franck formuliert, aber Aufmerksamkeit ist auch die grundlegenste Infrastruktur all unserer sozialen Beziehungen. Aufmerksamkeit ist die Währung jedes dividuellen In-Beziehung-Tretens und jede Beziehung erfordert ein gewisses Maß an Aufmerksamkeit. In einer soliden Beziehung ist man wechselseitig über beide Ohren in Aufmerksamkeit verschuldet.

Aufmerksamkeit macht, dass wir uns als ein „Gegenüber“ spüren. Aufmerksamkeit ist Anerkennung – zumindest der eigenen Existenz. Die Suche nach Aufmerksamkeit, egal ob privat, oder öffentlich, ist deswegen immer auch ein wichtiger Teil unserer Motivation.

10. Motivation ist das Orientierungsschema der Pfadselektion und das ist „messy“, denn alle bisher genannten Faktoren der Perspektive – die Suche nach Aufmerksamkeit, die Erlaubnisstrukturen, die Emotionen, die Pfadgelegenheiten, die Eindrücke, usw. spielen hier natürlich immer mit rein, aber dennoch lassen sich einige davon unabhängige, populäre Motivationsschema isolieren und betrachten.

Das Individuum zum Beispiel strebt oft nach „Individualität/Authentizität“, wobei die „Individualitäten“, die sich die Individuen einreden, nur heterogene Pfadgelegenheiten in einer größtenteils nur oberflächlich pluralistischen Pfadgelegenheitslandschaft sind. Daraus ergibt sich ein „Lockstep Individualismus“, ein Konzept, das der Linguist Adam Aleksic aus Krasse Links No 29 anhand von männlicher Namensgebung erklärt.

In diesem Video beschreibt er das Phänomen, dass Jungennamen in den USA immer häufiger mit „n“ enden und dieser Trend zur Uniformität lässt sich paradoxer auf einen Abgrenzungswillen zurückführen. Es wurden ganz viele neue Namen kreiert, aber meist welche, die auf „n“ enden, weil das irgendwie „low key“ männlich wahrgenommen wird. Das führte zu mehr Männern mit „n“ am Namensende, was den Eindruck verstärkte, etc. Network effects all over again.

Jedenfalls nennt man das wohl „Lockstep Individualism“ und ich musste herzlich lachen, aber dann fragte ich mich: gibt es einen Individualismus, der nicht lockstep ist? Ist nicht jede Abgrenzungsgeste bereits im lockstep mit all den anderen Abgrenzungsprojekten? Ist lockstep-Abgrenzung nicht auch irgendwie unser Thing?

Das, was Philosoph*innen seit Platon und Aristotelis, über Walter Benjamin zu René Girard als „Memisis“ identifizieren, ist einfach ein Effekt unseres Pfadopportunismus im Zusammenspiel mit unserer dividuellen Subjektivierung. Das äußert sich natürlich beim Kleinkind deutlicher, also in einer Phase wo man noch keine Infrastrukturen hat und nach allen beobachten Pfadgelegenheiten greift. Jedenfalls mehr als heute, wo sich unser Pfadopportunismus als „Lockstep-Individualismus“, der eigentlich einfach ein Dividualismus ist, in Form von Moden, Trends, Memes, Subkulturen, „Bürgerlichkeit“, oder der „Öffentlichen Meinung“ aggregiert.

Während die Motivation des Individuums also oft mit „Nutzenmaximierung“ beschrieben wird, ist die Motivation des Dividuums am einfachsten mit Will Storr, als „to get ahead und to get along“ umschrieben, also: Weiterkommen und Auskommen. Nur legen manche mehr Wert auf getting ahead und andere mehr auf getting along?

Dieses Navigationsschema führt bedauerlicherweise zu einem notwendigen Pfadopportunismus. Die Welt ist eng, das Leben kurz, man muss die Pfade nehmen, wie sie sich einem bieten, wobei die allgemeine Plausibilität eines Pfades in der Gesellschaft eine entscheidende Rolle spielt. Und ist man auf einem Pfad, werden die Kosten immer größer, die ein Exit bedeuten würde und so lässt man sich leiten, wie auf Schienen.

Hier ist die Schwierigkeit: Es braucht immer ein aktives „Nein“, um einen Pfad zu verlassen und dieses „Nein“ muss die Kosten der Pfadabweichung immer mit einpreisen. Deswegen gelingt das „Nein“ nur, wenn das Dividuum es schafft, einen alternativen Pfad emotional zu inszenieren, also zu imaginieren und ihn dem aktuellen Pfad vorzuziehen. Doch selbst wenn das gelingt: an den Schmerzen führt kein Weg drumrum.

11. Geschichte. Wie auch jedes Individuum, erzählen sich auch Dividuen, jedenfalls sofern sie subjektivieren. Aber während das Individuum sich als Protagonist seiner Welt erzählt, erzählt sich das Dividuum eher als höflicher Pfadopportunist. Als Überlebender in einer Welt mit anderen Überlebenden (siehe dazu Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World), auf der Suche nach Frieden und Sicherheit.

Weil sich die Welt ständig in das Dividuum eindrückt, verändert sie ständig auch seine Perspektive und Pfadgelegenheiten und ein Großteil seiner Zeit verbringt das Dividuum damit, Abhängigkeiten zu verlagern und neue Pfadgelegenheiten zu suchen, um verschwundende Pfadgelegenheiten durch andere und schlechte Pfadgelegenheiten durch bessere zu ersetzen, etc. Das heißt, das Leben des Dividuums ist meistens gar nicht so spannend und selten heldenhaft, aber erstens braucht es Geschichte, um zu planen, denn ohne Geschichte, ohne einen Ausgangspunkt und einen Pfad, kann man sich nicht in die Zukunft entwerfen. Der zweite Grund ist, dass sich das Divdiuum ohne die eigene Geschichte nicht von der Welt und vor allem den Erwartungen der anderen abgrenzen kann. Die eigene Geschichte ist immer eine Abgrenzungsgeschichte. Jede Geschichte ist anders, aber die Eckpunkte jeder Geschichte bestehen aus den Momenten, wo sind wir von den Erwartungen der anderen abgewichen sind, ob freiwillig oder unfreiwillig.

Die Geschichte reguliert das Handeln über den Blick des Anderen: Bei jeder Pfadgelegenheit, die wir nehmen, fragen wir uns, ob der Andere sie uns erlauben würde, was im Endeffekt heißt: Ob er die Geschichte kaufen würde, die wir uns selbst auftischen. Das ist der Mechanismus, der uns „ehrlich“ hält.

Geschichte und Geschichten beginnen immer dann, wenn von einer Erwartung abgewichen wird, weil sie erst durch Erwartungsabweichung notwendig wird und oft überzeugt die Geschichte nicht alle.

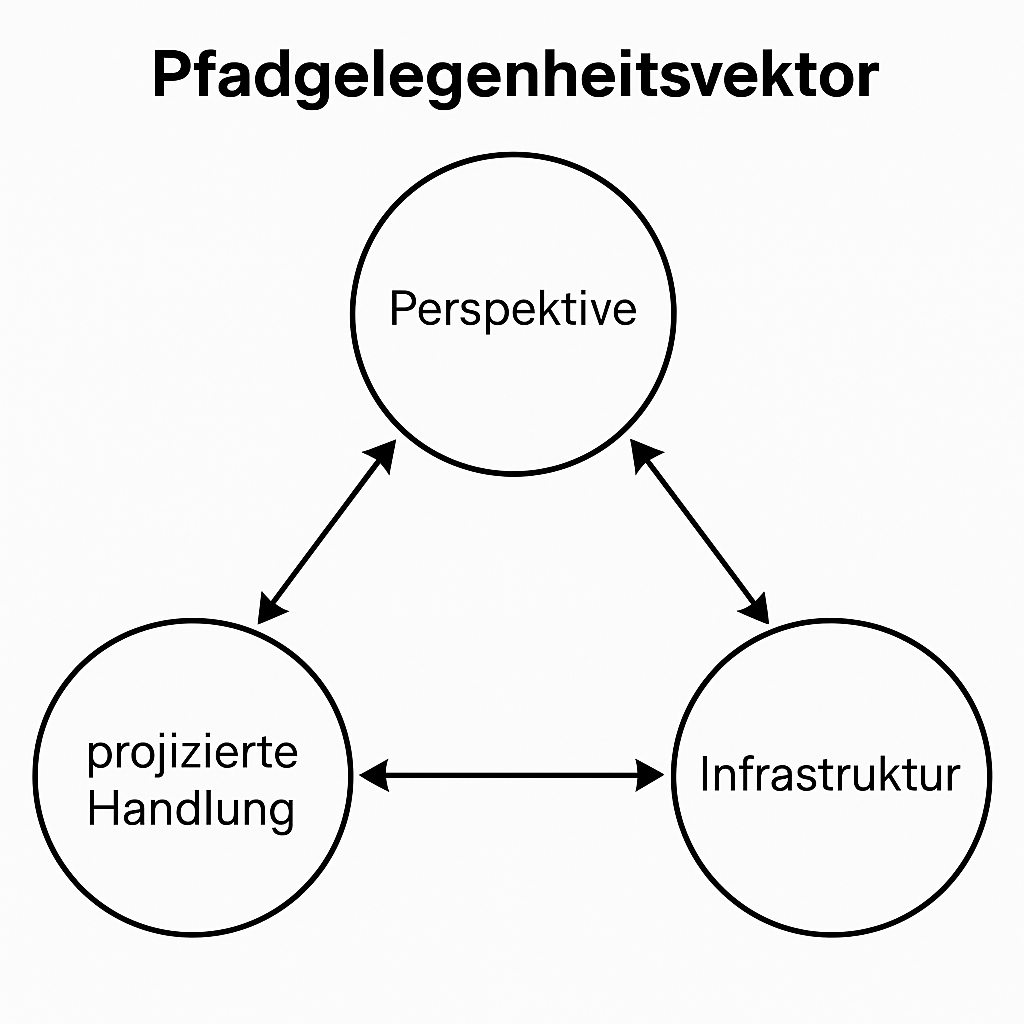

12. Pfadgelegenheits-Turing-Maschine. Bisher ist die Perspektive statisch, doch das ändert sich, wenn wir die Interdependenzen betrachten, die zwischen der Perspektive, der Infrastruktur (Pfadabhängigkeiten) und der projizierten Handlung (δ) existiert, die die Perspektive vorantreibt, den Ort in Geschichte verwandelt und die Geschichte zum nächsten Ort macht.

Im Pfadgelegenheits-Explainer führe ich die Pfadgelegenheits-Turing-Maschine so ein.

Aber hier ist der Trick: die ständige neu erzeugte Spannung zwischen den interdependenten Vektoren Perspektive, projizierte Handlung und Infrastruktur, treibt die Maschine voran.

Hier wie es doch eigentlich läuft: Die vorhandenen Infrastrukturen machen aus einer bestimmten Perspektive die projizierte Handlung einer Pfadgelegenheit plausibel, die, sobald sie genommen wurde, Teil der pfadabhängigen Infrastruktur wird, was wiederum die Perspektive um eine Pfadgelegenheit weiterschiebt, damit sie die nächste Pfadgelegenheit anvisieren kann.

Stellen wir uns vor, es ist Sommer und ihr wollt einen Sommerausflug nach München machen, denn Sommerausflüge nach München sind schön. Dafür muss man aber unterschiedliche pfadabhängige Pfadgelegegenheiten wahrnehmen, etwa „Ticket kaufen“.

Wir können uns das so vorstellen: Die Pfadgelegenheit „Ausflug nach München“ rückt die Pfadgelegenheit „Zugfahren“ in unsere Perspektive, die wiederum die Perspektive auf „Tickets Buchen“ verschiebt. Ist die bis dahin projizierte Handlung: „Tickets Buchen“ vollzogen, wandern die Tickets in die Infrastruktur und bereiten damit die Pfadgelegenheit des nächsten Schritts vor. Die Veränderung der Infrastruktur wiederum verschiebt die Perspektive, nämlich unter anderem, um eine Pfadgelegenheit weiter. Zu, z.B. Termin in den Kalender eintragen, Hotel buchen, oder zum Bahnhof kommen und dann geht der Spaß geht von vorn los. Und so kommt man Zug um Zug zum Zug und schließlich nach München.

P (Perspektive)

I (Infrastruktur)

δ (Handlung)

δ : (Pt, It) → (Pt+1, It+1)

Pt: „Tickets Buchen“ (aktueller Fokus)

It: Bahnwebsite, BahnInfrastruktur, Kreditkarte, Erwartungen

δ: Ausführung der Buchung

Pt+1: „zum Bahnhof kommen“, neues Perspektivfeld.

It+1: Bisherige Infrastruktur + Tickets

Mit der Pfadgelegenheits-Turing-Maschine wird der dividuelle Perspektiv-Entwurf dynamisch.

Nimmt das Dividuum eine Pfadgelegenheit, wird der Plan aktualisiert und shiftet einen Task weiter und aus dem vorherigen Ort mit seinen Pfadgelegenheiten wird pfadabhängige Geschichte/Infrastruktur. Die Perspektive rückt ebenfalls vor, so dass aus „Geschichte“ wiederum der neue Ort wird, von dem aus das Dividuum handelt und spricht.

Beobachtungen: Das Dividuum in seiner Welt

Weil alle Dividuen überlappende materielle und semantische Welten bewohnen, ergeben sich darin Topologien: Verdichtungen, Erhebungen, Muster, Hubs, Cluster, Barrieren, Flüsse, Staus, Infarkte, Formationen, Abkürzungen, Highways oder Backbones und Netzwerkzentralitäten und ihre Provinzen. In der Beschreibung des Netzwerks der Pfadgelegenheiten können wir viel über die Gesellschaft erfahren.

Hier ein paar nützliche Datenpunkte, die ich im Newsletter über die Zeit über das Dividuum und seinen Weltbezug trianguliert habe:

- KL29: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die die Welt beobachten, sondern Dividuen, die einander beobachten, wie sie die Welt beobachten, ist Öffentlichkeit ein Klangkörper, den wir alle miteinander bespielen.

- KL30: Weil wir nicht einfach gewalttätige Individuen sind, sondern Dividuen, die einander Gewalt erlauben (siehe auch Milgram), kommt jede Gewalt mit ihrer Erlaubnisstruktur.

- KL31: Weil wir keine generalisierenden Individuen sind, sondern Dividuen die gemeinsam an einer sozialen Skulptur arbeiten, die wir wechselseitig als „Wirklichkeit“ beglaubigen, verwenden wir einander als Erlaubnisstruktur für unsere Generalisierungen.

- KL34: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, deren „Mind“ über psychologische Stimuli „manipulierbar“ ist, sondern Dividuen, die sich aneinander orientieren, funktioniert echte Manipulation nicht als Operation am Individuum, sondern über Modifikation der Öffentlichkeit.

- KL35: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die die Welt beobachten, sondern Dividuen, die ihre Beobachtungen dazu nutzen, aufgeschnappte Erzählungen zu plausibilisieren, tragen Milliarden Schmerzerinnerungen als verteilte Privatempirie die Thesen der Rogannomics.

- KL39: Weil Silicon Valley Oligarchen keine ruchlosen Individuen sind, sondern Dividuen, die sich die Ruchlosigkeit voneinander abgucken, borgt sich Mark Zuckerberg die männlich-hegemoniale Erlaubnisstruktur von Elon Musk, wie Ryan Broderick aufzeigt.

- KL40: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die sich einfach entschließen können, die Matrix zu verlassen, sondern Pfadopportunisten, die immer nur den plausiblen Pfaden folgen, die sie vor sich sehen, brauchen wir Infrastruktur, um der Matrix zu entfliehen.

- KL41: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die mit „kognitiven Verzerrungen“ ihres eigentlich „objektiv-rationalen“ Denkapparates kämpfen, sondern dividuelle Pfadopportunisten, die einander auf Deutungspfaden folgen, bleiben wir auf die Deutungsangebote angewiesen, die uns materiell, semantisch und sozial zugänglich sind.

- KL53: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die einfach „verdrängen“, sondern Dividuen, die sich über ihre Verdrängungserzählungen zu semantischen Verdrängungsgemeinschaften verbinden, basieren die meisten echten Verschwörungen auf Groupthink.

- KL60: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die Entscheidungen im luftleeren Raum unseres „Minds“ fällen, sondern Dividuen deren Verbindungen die Entstehung von anderen Verbindungen beeinflussen, sind wir in jeder Lebenslage Netzwerkeffekten ausgesetzt.

- KL62: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die ihre Überzeugungen aus ihrem Inneren schöpfen, sondern Dividuen, die ihre Überzeugungen aus den Überzeugungen von anderen triangulieren, verändert es unseren Orientierungssinn, wenn wir „normale Menschen“ in der Öffentlichkeit dumme Dinge sagen hören.

- KL62: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die die Welt beobachten, sondern Dividuen, die einander beobachten, wie sie die Welt beobachten, akkumuliert sich unsere Aufmerksamkeiten dort, wo wir die Aufmerksamkeit anderer erwarten.

- KL63: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die einfach Sinn in ihrer Arbeit sehen, sondern Dividuen, die sich durch Einsatz ihrer Aufmerksamkeit gegenseitig den Sinn in ihrer Arbeit beglaubigen, schickt uns die Versloppung der Welt in eine Verantwortungslosigkeits-Spirale.

- KL65: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die die Welt beobachten, sondern Dividuen, die einander Beobachten, wie sie die Welt beobachten, können wir uns nicht einfach „eigene Gedanken“ machen, sondern sind gefangen in dem jeweils wechselseitig beglaubigten semantischen Raum, den wir „Wirklichkeit“ nennen.

- KL68: Weil wir keine Individuen sind, die entweder egoistisch oder solidarisch sind, sondern Dividuen, die einander beim egoistisch oder solidarisch sein zuschauen, und daraus ihre Schlüsse für ihre Strategie ziehen, hat Trump eine Möglichkeit gefunden, die halbe gesellschaftliche Elite der USA – immer einen nach dem anderen – in die Knie zu zwingen.

Alles was das Dividuum „kann“, „ist“ oder „hat“ ist entweder aus seiner ständigen Anpassungsleitung an die Umwelt entstanden, oder aus der Anpassungsleistung der Umwelt an seine Pfadbedürfnisse. Das Dividuum ist gleichzeitig Medium von Strukturen und Strukturgenerator (Pfadgelegenheiten vorausgesetzt).

Doch hier ist das Problem: Sobald wir Fragen, was das Dividuum „ist“, d.h. woraus es besteht, wie es abgegrenzt ist, wie es aufgebaut ist, usw., stellen wir es uns schon falsch vor.

Das Dividuum und seine Pfadgelegenheiten ist der oder das Andere, bei Levinas. Wir sind aufgefordert, uns in das Dividuum hineinzuversetzen, ihm gastfreundschaftlich statt zu geben, aber wir werden niemals alle seine Netzwerke kennen und selbst wenn. Das Dividuum ist niemals abgeschlossen und auch apriori unabschließbar, denn seine Pfadgelegenheiten sind für die Zukunft offen. Das Dividuum ist das Andere in uns, die unabschließbare Differenz unseres eigenen Handlungspotenzials – das Unverfügbare, das sich nicht messen, nicht besitzen, nicht zentralisieren lässt. Jedenfalls nie vollständig.

Genau deswegen ist das Dividuum ein antifaschistischer Subjektentwurf. Aber wie das bei linken Projekten immer so ist: Es ist leider ein unvollständiger Subjektentwurf. Es ist quasi das Individuum als entkernte Ruine und ohne seine Agency.

An einer anderen Stelle schreibt Deleuze im Postskriptum:

Weder zur Furcht, noch zur Hoffnung besteht Grund, sondern nur dazu, neue Waffen zu suchen.

Das Dividuum allein ist noch keine Waffe. Damit das Dividuum handlungsfähig wird, braucht es eine oder mehrere Pfadgelegenheiten. Erst mit der (semantischen) Pfadgelegenheit zusammen, vervollständigt sich der alternative Subjektentwurf.